Nils Reiter

Annotating Coreference Chains (Part 1)

We have recently started to annotate coreference chains in dramatic texts. In this loose series of blog posts, we will discuss interesting findings and examples. The first post covers some background and technical setup.

Table of contents

Introduction

The phenomenon of coreference describes the situation that multiple words in a text refer to the same (real world) entity: They co-refer, hence the name. Prototypical examples can easily be created:

[Mary]1 bought [a car]2. [The car]3 is green and [it]4 has four wheels.

In the above example, two discourse entities are mentioned: Mary and her new car. Mary is mentioned once, by her name (marked with the subscript 1). The car, however, is mentioned multiple times, marked with subscripts 2 to 4, all are referring to the same entity. Linguistically, we can distinguish three kinds of mentions:

- Proper names (Mary)

- Pronouns (it)

- Noun phrases (a car, the car)

Noun phrases (NPs) can further be distinguished into definite and indefinite noun phrases. A car is an indefinite NP, because it starts with an indefinite article (and it does not refer to a specific car). The car refers to one specific car that either has been introduced before or is globally known and unique (in many context, the president can be used without introduction).

Coreference has been annotated on newspaper corpora, most prominently (for German) in the TüBa-D/Z. In the context of CLARIN-D, a small set of coreference data has been annotated on non-standard domains (NoSta-D). For both corpora, annotation guidelines have been released: TüBa-D/Z, NoSta-D, but the latter are mostly based on the former.

Our goal for the annotation is to create a gold standard in order to evaluate automatic approaches for coreference resolution. We are dealing with literary texts and in particular dramatic texts. Therefore, we expect a certain need to refine, enhance and especially adapt or the guidelines to this domain. Since it contains different text types (e.g., dialogue, stage instructions) and mentions are spread over and between text type boundaries, dramatic texts offer a particularly challenging test field for the annotation of coreference. To be able to re-use existing resources (corpora and tools), we aim for annotations that are compatible to the TüBa-D/Z-guidelines.

Corpus

We started annotation of two dramatic texts, Lessings Miß Sara Sampson and Schillers Die Räuber. Both are rooted in the middle to late 18th century and represent different, though very popular elements of german drama history: MIß Sara Sampson represents the genre Bourgeoise Tragedy and Die Räuber represents the era Sturm und Drang. Both are available as part of the GerDraCor, which we forked for this purpose. GerDraCor is formatted in TEI XML and relatively clean, which makes it a good basis for such annotations. In particular, GerDraCor assigns each character a unique identifier, which we can also use for the annotations:

...

<person xml:id="sir_william">

<persName>SIR WILLIAM</persName>

</person>

...

Speakers within the text are also disambiguated using these ids:

...

<sp who="#sir_william">

<speaker>SIR WILLIAM.</speaker>

<l> Nun so laß mich.</l>

</sp>

...

(It may seem here that mapping the speaker attribution to the dramatis personae is a trivial task, but it is not).

Representation in TEI

We intend to make our annotations available to the community. The easiest way to do that is to add them into the TEI-XML from GerDraCor.

Of course, TEI provides mechanisms for representing co-reference: The element <name> (documentation) can be used to mark proper names, and the attribute @who (doc) can be used to store the identifier of the mentioned entity. This makes annotating proper names straightforward:

<sp who="#mellefont">

<speaker>MELLEFONT.</speaker>

<l> Ach <name ref="#sara">Sara</name>, wenn Ihnen alle zeitliche Güter so gewiß wären, als Ihrer Tugend die ewigen sind – –</l>

</sp>

For other mentions (pronouns, noun phrases), we decided to use the <rs> element (“referencing string”, doc) to mark the mention and again the @who attribute to make it unambiguous. “Ihnen”, in the example above, would then be annotated as follows:

<sp who="#mellefont">

<speaker>MELLEFONT.</speaker>

<l> Ach <name ref="#sara">Sara</name>, wenn <rs ref="#sara">Ihnen</rs> alle zeitliche Güter so gewiß wären, als Ihrer Tugend die ewigen sind – –</l>

</sp>

This obviously only works for discourse entities that already have identifiers (which are the characters mentioned in the dramatis personae). The annotation guidelines, however, specify to annotate every discourse entity which is referred to at least twice. I.e., as soon as one discourse entity is mentioned multiple times, we add a coreference link, even if the entity is irrelevant/uninteresting for the text. We therefore also need a way to create new identifiers:

If a new discourse entity is mentioned first (e.g., with a indefinite NP), a new identifier is created on the fly, using the @xml:id attribute. This can be done in <name> and <rs> elements.

<sp who="#waitwell">

<speaker>WAITWELL.</speaker>

...

<rs xml:id="böse_leute">Böse Leute</rs> suchen immer das Dunkle, weil <rs ref="#böse_leute">sie</rs> böse Leute sind. Aber was hilft es <rs ref="#böse_leute">ihnen</rs>, wenn <rs ref="#böse_leute">sie</rs> sich auch vor der ganzen Welt verbergen könnten?

...

</sp>

This setup allows representing the basic concepts of coreference, and is relatively straightforward. It has its limits though: Linguistic coreference annotations distinguish between different types of links between mentions (coreferential, anaphoric, part_of). Since we are not encoding binary relations between words, this can not be encoded in an easy way. There is simply no element to attach attributes to.

Annotation Tools

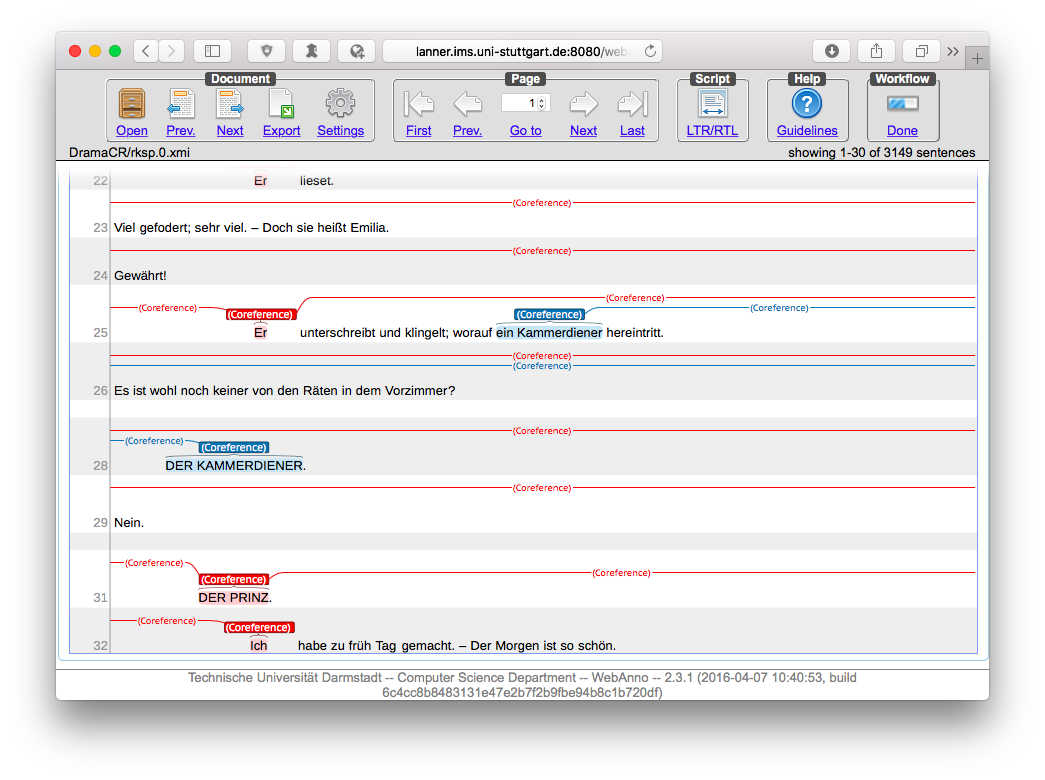

Coreference annotations in NLP would typically make use of annotation tools (such as WebAnno). Annotation tools can relieve annotators of a lot of minor decisions and tedious work (e.g., defining new ids for new discourse entities), and make the resulting coreference chains much easier to see, inspect, evaluate and correct:

Screenshot of WebAnno. Shown are the first few sentences of Lessings Emilia Galotti.

However, most annotation tools that are used in the NLP community are working with stand-off annotations. Annotations are not stored as in TEI, but separately from the original text, with their begin and end character positions. This has tremendous advantages for tool development and annotation handling, since one does not need to care about the correct nesting of the XML tags. Unfortunately, this makes using existing annotation tools impossible here. Our annotators therefore mark the coreferences directly in the XML markup. First impressions show that this works better than expected (in terms of XML encoding issues), but it makes annotation much slower (and is definitely not fun). If you have suggestions, I’d be happy if you drop me an email.

The next part of the series will cover findings from the annotations in the first act of the Miß Sara Sampson.